Fire Alarm in the Barracks!

At 4:00 AM the fire alarm screamed throughout the barracks. As happened every time the barracks were to be inspected, about 60 sleepy-eyed, blanket-wrapped airmen exited each of the four doors of the two story barracks--60 stumbled out of the top north door, 60 from the bottom north door, 60 from the top south door and 60 from the bottom south door. We always stood outside on the grass for five to ten minutes, and, then, re-entered the barracks to start the day and prepare for the upcoming inspection. This was probably our 8th inspection and and we all knew the routine.

But, on this cold Wednesday morning November 25, 1961--there was a variation. Some blanket-wrapped, bare-footed airman on the second floor, north end stood in the hallway and said we don't need to go outside--we're already awake, we know the drill. Someone else agreed and stood by his door encouraging others to stay put as well. Some got to the north end fire exit stairway, saw how cold it was outside and quickly agreed with those prescient young men who stood their ground in the hallway and refused to go outside. When I came out of my door, about 59 airmen were standing in the hallway assuring each other that this was the wisest thing to do--why did it take us so long to figure this out? I quickly saw the logic and joined these north end, top floor fire drill miscreants.

We stood in the hallway and talked until we saw the airmen on the south end, top floor of the building re-entering their doorway. We marveled at our cleverness, returned to our rooms and started our day of showering, shaving, dressing and polishing everything that could be polished for inspection. It would be a good day and the upcoming four-day Thanksgiving weekend would be even better. Life is good.

But, maybe not. MSgt Freeman T. Evans--without knocking--opened the door of our room, looked in at the three of us and said, "My office." We looked at each other and walked into the hallway. Sgt Evans was headed downstairs to his office at the center of the first floor of the barracks. Sixty variously-dressed airmen stood in front of Sgt. Evans desk. "Why didn't you go outside like you're supposed to during a fire drill?" No one volunteered an answer. It was a very quiet five seconds. Then, Sergeant Evans said, "Go get your Class A passes and put them right here," tapping the corner of his desk. "You can come get your pass back on Monday." He grabbed and began reading some important-looking paper indicating to each of us that this discussion was over.

Thirty somewhat dazed young airmen walked upstairs, rifled their wallets, looked lovingly at their Class A Pass and then headed back downstairs. The stack of cards on Sgt Evans desk was growing when I got there but I dreamed that he would say something like, "Keep your card, I was just making a point, go ahead and enjoy the Thanksgiving weekend."

But, no. It was done. Sixty young airmen would spend Thanksgiving weekend on base--no off-base movies, no off-base travel, no off-base restaurants, no off-base visits, no off-base dates. We were stuck! Some of us had planned to go to a nearby home--Doris and Ralph Hannah had invited some of us to their home for Thanksgiving dinner--and, a few airmen had dates for the weekend. Nobody had expected to spend the entire Thanksgiving weekend on base! (Although Air Police--APs--rarely checked Class A Passes off base, there was always the chance of getting checked while leaving or entering the base through one of the many armed and guarded gates. Yep, we were stuck on base for Thanksgiving weekend.)

Jailbreak

On Wednesday evening, after many airmen in other parts of our barracks had departed for their long weekend, Ed Kinney, Bill Macklin and I met in a secluded area and I presented my jailbreak plan.

Today, I had reserved one of the Aero Club's Cessna 172s for noon Thanksgiving Day. My plan was this: at noon on Thanksgiving Day, we would take off from McConnell AFB, fly to Wichita's Mid-Continent Airport, bum a ride to our favorite restaurant, enjoy the Thanksgiving dinner that we had planned weeks ago, bum a ride back to Mid-Continent and then fly back to the Air Base. We would never pass through one of the base's guarded gates.

The next day, Thanksgiving morning was bright and clear.We boarded our Cessna 172, I taxied out to 12,000 foot long runway 18R and we departed the base. Our day went as planned, Thanksgiving dinner was better than expected, and, late Thursday afternoon back at the base, we walked into the barracks day room where 50 or so bored and frustrated airmen were arguing about which game to watch on TV. We looked around, pitied their predicament and walked back to our rooms to contemplate one of the finest, adrenaline-fueled Thanksgiving dinners so far in our young lives.

Freeman T. and the APs--fooled again!

Growing up the fun way. Walking with my grandmother to the outhouse on cold, snowy nights, embarrassed that I was wearing a flour sack shirt on the day of grade school photos, soloing airplanes in my teens, programming computers in the US Air Force, earning five FAA pilot ratings and an MBA, traveling to 23 countries, sharing the world with foster children and Little Brothers, and living the advice that I give all of those children: learn much, work hard, do good, have fun.

Sunday, October 20, 2013

Saturday, October 19, 2013

Glider test pilot - first flight in single-seat Jantar Standard sailplane

It was about noon on a beautiful Saturday September 4, 1993. At the Panhandle, Texas airport, Dick Wilfong and I were standing in the bright sunshine admiring a beautiful 1977 SZD-41A Jantar Standard sailplane. I looked at Dick and he looked at me. "Now, who's going to fly it?" we asked each other at the same time.

Dick and I had just assembled our sleek, white, fiberglass, high-performance, retractable-gear, T-tail, single-seat Jantar Standard sailplane and it was ready to fly. However, neither of us had ever flown this Jantar sailplane before. Actually, neither of us had ever flown any Jantar sailplane before. As a matter of fact, neither of us had ever seen any Jantar sailplane fly at all. But, it looked good. The previous owner told us it would fly. All the pieces went together as advertised, and, after we assembled it, we didn't have any pieces left! It must be ready to fly.

Well, the tow-plane pilot was waiting and the Jantar looked like it was ready to go. Now what do we do?

1977 SZD-41A Jantar Standard Glider N11XH at the Panhandle, Texas airport

...all dressed up and waiting for a pilot.

-----

-----

For 6 months, Dick Wilfong and I had looked for a sailplane to buy. We traveled to Dallas, but didn't like any of the 'for sale' sailplanes we saw there.

A few weekends later, Dick and I traveled to the Decatur, Texas airport and met a gentleman from Louisiana. He had a 1977 Jantar Standard and had agreed to meet us about halfway between our two home cities to show us his sailplane.

We peeked into the long glider trailer. (Glider, sailplane, we use the term interchangeably.) The plane looked good, the trailer and plane were clean. We needed a closer look.

I'll not go into lots of detail here, but, we pulled the fuselage halfway out of the trailer, removed and attached one wing, attached a wing dolly to that wing in order to keep the aircraft level, removed and attached the other wing, pulled the glider completely out of the trailer, and, then, removed and attached the horizontal stabilizer. During this process, the owner gave us continuous detailed instructions and answered all of our questions. When the glider was assembled, we took turns sitting in the single-person cockpit where we buckled the 4-point seat belt; latched the canopy; worked the stick, rudder, brakes, spoilers; did not retract the single, center-wheel landing gear; operated the tow-rope release handle; and switched and clicked all of the electrical equipment.

When we had seen everything, we returned the aircraft to the trailer reversing the order that the pieces had been taken out. Everything was smooth and simple; all made sense. Of course, the owner and long-time pilot of this sailplane made everything go smoothly, but, Dick and I did catch on fast.

Dick and I ran out of questions and had no qualms about anything. It was a deal. We shook hands with the seller, paid the man, hooked the trailer up to my white Cressida and headed for Amarillo. We had a sailplane.

-----

Two weeks later, we faced our dilemma: "Now, who's going to fly it?"

Dick said, "Want to flip a coin?"

I said, "Great."

Dick took out a coin and said, "Heads or tails?"

I said, "Wait, does the winner fly or does the winner watch?" We laughed and agreed that the winner would fly.

"Heads," I said.

Heads it was.

First flight

Dick and I pushed the Jantar to the north end of runway 17 at the Panhandle Airport. We removed the tail and wing dollies and I walked around the plane one more time. Everything was solid, all control surfaces reacted correctly to positive and negative control inputs, we had streamlined all open seams with white friction tape, battery was fully charged, the removable windshield was clean, parachute had a current inspection date, main tire was properly inflated, tow rope hooked and unhooked properly--I was ready to hop aboard.

I got into the plane and buckled in. Dick picked up the canopy, set it in place and I locked both sides. Dick hooked the tow rope to the nose hook, pulled it tight and signaled me to released it. I did and it worked fine. Dick, hooked the tow rope up again and signaled for the tow plane to take out the slack in the rope.

This is the club's Cessna 182 tow plane. On soaring days, if I was not flying a glider, I was flying the tow plane. (If you click the photo to enlarge it, you can see the tail hook at the bottom of the airplane's tail. Typically, the glider pilot, at 2,000 AGL, released from the tow rope and headed out. The tow plane then drug the tow rope back to the airport, and, at about 200 feet over the approach end of the runway, dropped the tow rope so that it fell right onto the runway numbers. By the time the tow plane landed and taxied back to the starting point on the runway, the ground crew had positioned the next glider, hooked the tow rope to the nose of the glider and were waiting to hook the rope to the tow plane.)

The tow plane taxied ahead until the tow plane signaller raised his arms and crossed his wrists. Now, the tow rope laid flat on the runway and had no curls. I checked the instruments. Dick held up the tail dolly so that I could see and verify that it had been removed from the plane (you do not want to take off with the tail dolly attached to the plane). The tow plane signaller stood expectantly beside the tow plane looking back at the glider sitting 200 feet behind. Eight glider pilots stood beside the runway watching and waiting. The take off checklist was complete and I had nothing else to do but fly.

With my feet on the rudder pedals, my right hand on the stick and my mind focused laser-like on the scene through the windshield, I quickly glanced at Dick, who was standing at my right wing-tip, and gave him a thumbs up. Dick stooped down and lifted the right wing tip until the wings were level. Only by pulling the tow rope release handle now can I stop the next steps.

The tow plane signaller saw the wings become level and began slinging his left arm in a complete, vertical circular motion. A light cloud of dust rose behind the tow plane, the rope rose from the ground and we were moving forward. Dick, holding the wing tip, walked and then ran for 5 to 10 seconds and then let go. With the main gear and tail wheel still on the ground, I steered the glider--with aileron, rudder and elevator--down the runway behind the tow plane. Gently pushing forward on the stick, I raised the tail wheel. Keeping wings level, fuselage straight and nose level, we gained speed. At some speed--probably around 40 to 50 knots (you do not look at the instruments much during takeoff)--the plane lifted off the ground.

Now the hard part

I was now flying the glider but the tow plane needed another 10 to 20 seconds to get into the air. Until the tow plane leaves the ground, I must fly perfect formation behind him--rope taut, wings level, same altitude and directly behind the tow plane's tail. I must nail it! (The high-performance fiberglass 'rocket' glider wants to climb like, well, a rocket, but I must climb no higher than the tow plane. If I zoom up, I'll lift the tail of the tow plane making the tow plane uncontrollable. And, if I move left or right, the tow plane becomes uncontrollable. And, if I intentionally or unintentionally deploy the spoilers, drag increases so much that the tow plane can't reach takeoff speed. If any of those things happen, the tow plane pilot will--as agreed to beforehand--immediately release his end of the tow rope, fly away freely and bid me farewell--have a nice day! Understood rule between the tow-plane pilot and the glider pilot--hurt yourself if you wish but you're not going to hurt us both.)

I stayed behind the tow plane as he gained speed and lifted off the ground. With both of us in the air, I kept the rope taut, stayed at his altitude and matched his bank during turns. He circled the airport once while heading for a release altitude of two thousand feet above the ground and he stayed close to the airport just in case I screwed up and caused a rope break. See photo and note below.

Note - On August 15, 1993, while flying a two-seater Grob 103 in Hobbs, New Mexico (see photo above), I did have a rope break at 500 feet. I circled back, landed, got a new tow rope and flew 7 more flights trying very hard not to do that again. (While climbing out on tow, the glider pilot periodically glances at the altimeter, and, upon passing 400 feet, says, out loud, "Four hundred feet." Glider pilot rule: if you have a rope break before you have said, "Four hundred feet," you land straight ahead no matter what. Everything might be okay. If you have a rope break after you have said, "Four hundred feet," you immediately turn into the wind, complete your turn toward the airport of departure, and, land. Everything will be okay!)

During tow, we passed through some rising air and the tow pilot then planned our circuitous, rising flight so that I would be in that rising air when our little two-plane formation reached an altitude of 2,000 feet above the ground. The tow plane pilot and I both knew what was happening because we were both glider and tow plane pilots and we both knew that we were looking for rising air.

At 2,000 feet above the ground, about 3 miles southwest of the Panhandle airport, on a southwest heading, I decided that this thermal would work, so, I released the tow rope, and, at that moment I began a steep climbing turn to the right, and, the tow plane--dragging the 200 foot tow rope--began a descending left turn that would take him away from me. I immediately retracted the landing gear to reduce drag. (During tow, we leave the gear down causing some drag, because, the slick, high performance glider can too easily overtake the tow plane.)

The rest is history. I flew the beautiful Jantar Standard for 42 minutes that day--climbing and turning like a silent beautiful, white bird over the clear blue skies of Texas Panhandle. During the next few years, I would take this sailplane up to 22,000 feet and make flights longer than three hours. Like a dream. But, it was real. I could be a test pilot!

Dick and I had just assembled our sleek, white, fiberglass, high-performance, retractable-gear, T-tail, single-seat Jantar Standard sailplane and it was ready to fly. However, neither of us had ever flown this Jantar sailplane before. Actually, neither of us had ever flown any Jantar sailplane before. As a matter of fact, neither of us had ever seen any Jantar sailplane fly at all. But, it looked good. The previous owner told us it would fly. All the pieces went together as advertised, and, after we assembled it, we didn't have any pieces left! It must be ready to fly.

Well, the tow-plane pilot was waiting and the Jantar looked like it was ready to go. Now what do we do?

1977 SZD-41A Jantar Standard Glider N11XH at the Panhandle, Texas airport

...all dressed up and waiting for a pilot.

-----

Here are the aircraft specs from Wikipedia:

General characteristics

Crew: 1

Length: 7.11 m (23 ft 4 in)

Wingspan: 15 m (49 ft 2 ½ in)

Height: 1.51 m (4 ft 11 in)

Wing area: 10.66 m2 (114.75 ft2)

Aspect ratio: 21.1

Wing profile: NN 8

Empty weight: 244 kg (538 lb)

Gross weight: 360 kg (794 lb), with ballast 460 kg (1,014 lb)

Performance

Maximum speed: 250 km/h (155 mph)

Stall speed: with ballast 80km/h (50 mph), without ballast 68 km/h (42.25 mph)

G limits: * without ballast 5.3 / -2.65

with ballast 4.14 / -2.5

ultimate 7.95 / -3.98

Maximum glide ratio: 38 @ 92 km/h (57 mph) no ballast, 38 @ 105.2 km/h (65 mph) with ballast

Rate of sink: with ballast 0.69 m/s (136 ft/min), without ballast 0.6 m/s (118 ft/min)

How Dick and I ended up wondering who was going to fly this sailplane

For 6 months, Dick Wilfong and I had looked for a sailplane to buy. We traveled to Dallas, but didn't like any of the 'for sale' sailplanes we saw there.

Midlothian, Texas (near Dallas) is a great glider airport but, this weekend,

Dick (hatless) and I found no used sailplane that we wanted to buy.

A few weekends later, Dick and I traveled to the Decatur, Texas airport and met a gentleman from Louisiana. He had a 1977 Jantar Standard and had agreed to meet us about halfway between our two home cities to show us his sailplane.

We peeked into the long glider trailer. (Glider, sailplane, we use the term interchangeably.) The plane looked good, the trailer and plane were clean. We needed a closer look.

I'll not go into lots of detail here, but, we pulled the fuselage halfway out of the trailer, removed and attached one wing, attached a wing dolly to that wing in order to keep the aircraft level, removed and attached the other wing, pulled the glider completely out of the trailer, and, then, removed and attached the horizontal stabilizer. During this process, the owner gave us continuous detailed instructions and answered all of our questions. When the glider was assembled, we took turns sitting in the single-person cockpit where we buckled the 4-point seat belt; latched the canopy; worked the stick, rudder, brakes, spoilers; did not retract the single, center-wheel landing gear; operated the tow-rope release handle; and switched and clicked all of the electrical equipment.

When we had seen everything, we returned the aircraft to the trailer reversing the order that the pieces had been taken out. Everything was smooth and simple; all made sense. Of course, the owner and long-time pilot of this sailplane made everything go smoothly, but, Dick and I did catch on fast.

Dick and I ran out of questions and had no qualms about anything. It was a deal. We shook hands with the seller, paid the man, hooked the trailer up to my white Cressida and headed for Amarillo. We had a sailplane.

-----

Two weeks later, we faced our dilemma: "Now, who's going to fly it?"

Dick said, "Want to flip a coin?"

I said, "Great."

Dick took out a coin and said, "Heads or tails?"

I said, "Wait, does the winner fly or does the winner watch?" We laughed and agreed that the winner would fly.

"Heads," I said.

Heads it was.

-----

First flight

Dick and I pushed the Jantar to the north end of runway 17 at the Panhandle Airport. We removed the tail and wing dollies and I walked around the plane one more time. Everything was solid, all control surfaces reacted correctly to positive and negative control inputs, we had streamlined all open seams with white friction tape, battery was fully charged, the removable windshield was clean, parachute had a current inspection date, main tire was properly inflated, tow rope hooked and unhooked properly--I was ready to hop aboard.

I got into the plane and buckled in. Dick picked up the canopy, set it in place and I locked both sides. Dick hooked the tow rope to the nose hook, pulled it tight and signaled me to released it. I did and it worked fine. Dick, hooked the tow rope up again and signaled for the tow plane to take out the slack in the rope.

-----

This is the club's Cessna 182 tow plane. On soaring days, if I was not flying a glider, I was flying the tow plane. (If you click the photo to enlarge it, you can see the tail hook at the bottom of the airplane's tail. Typically, the glider pilot, at 2,000 AGL, released from the tow rope and headed out. The tow plane then drug the tow rope back to the airport, and, at about 200 feet over the approach end of the runway, dropped the tow rope so that it fell right onto the runway numbers. By the time the tow plane landed and taxied back to the starting point on the runway, the ground crew had positioned the next glider, hooked the tow rope to the nose of the glider and were waiting to hook the rope to the tow plane.)

-----

The tow plane taxied ahead until the tow plane signaller raised his arms and crossed his wrists. Now, the tow rope laid flat on the runway and had no curls. I checked the instruments. Dick held up the tail dolly so that I could see and verify that it had been removed from the plane (you do not want to take off with the tail dolly attached to the plane). The tow plane signaller stood expectantly beside the tow plane looking back at the glider sitting 200 feet behind. Eight glider pilots stood beside the runway watching and waiting. The take off checklist was complete and I had nothing else to do but fly.

With my feet on the rudder pedals, my right hand on the stick and my mind focused laser-like on the scene through the windshield, I quickly glanced at Dick, who was standing at my right wing-tip, and gave him a thumbs up. Dick stooped down and lifted the right wing tip until the wings were level. Only by pulling the tow rope release handle now can I stop the next steps.

The tow plane signaller saw the wings become level and began slinging his left arm in a complete, vertical circular motion. A light cloud of dust rose behind the tow plane, the rope rose from the ground and we were moving forward. Dick, holding the wing tip, walked and then ran for 5 to 10 seconds and then let go. With the main gear and tail wheel still on the ground, I steered the glider--with aileron, rudder and elevator--down the runway behind the tow plane. Gently pushing forward on the stick, I raised the tail wheel. Keeping wings level, fuselage straight and nose level, we gained speed. At some speed--probably around 40 to 50 knots (you do not look at the instruments much during takeoff)--the plane lifted off the ground.

Now the hard part

I was now flying the glider but the tow plane needed another 10 to 20 seconds to get into the air. Until the tow plane leaves the ground, I must fly perfect formation behind him--rope taut, wings level, same altitude and directly behind the tow plane's tail. I must nail it! (The high-performance fiberglass 'rocket' glider wants to climb like, well, a rocket, but I must climb no higher than the tow plane. If I zoom up, I'll lift the tail of the tow plane making the tow plane uncontrollable. And, if I move left or right, the tow plane becomes uncontrollable. And, if I intentionally or unintentionally deploy the spoilers, drag increases so much that the tow plane can't reach takeoff speed. If any of those things happen, the tow plane pilot will--as agreed to beforehand--immediately release his end of the tow rope, fly away freely and bid me farewell--have a nice day! Understood rule between the tow-plane pilot and the glider pilot--hurt yourself if you wish but you're not going to hurt us both.)

I stayed behind the tow plane as he gained speed and lifted off the ground. With both of us in the air, I kept the rope taut, stayed at his altitude and matched his bank during turns. He circled the airport once while heading for a release altitude of two thousand feet above the ground and he stayed close to the airport just in case I screwed up and caused a rope break. See photo and note below.

-----

Note - On August 15, 1993, while flying a two-seater Grob 103 in Hobbs, New Mexico (see photo above), I did have a rope break at 500 feet. I circled back, landed, got a new tow rope and flew 7 more flights trying very hard not to do that again. (While climbing out on tow, the glider pilot periodically glances at the altimeter, and, upon passing 400 feet, says, out loud, "Four hundred feet." Glider pilot rule: if you have a rope break before you have said, "Four hundred feet," you land straight ahead no matter what. Everything might be okay. If you have a rope break after you have said, "Four hundred feet," you immediately turn into the wind, complete your turn toward the airport of departure, and, land. Everything will be okay!)

-----

During tow, we passed through some rising air and the tow pilot then planned our circuitous, rising flight so that I would be in that rising air when our little two-plane formation reached an altitude of 2,000 feet above the ground. The tow plane pilot and I both knew what was happening because we were both glider and tow plane pilots and we both knew that we were looking for rising air.

At 2,000 feet above the ground, about 3 miles southwest of the Panhandle airport, on a southwest heading, I decided that this thermal would work, so, I released the tow rope, and, at that moment I began a steep climbing turn to the right, and, the tow plane--dragging the 200 foot tow rope--began a descending left turn that would take him away from me. I immediately retracted the landing gear to reduce drag. (During tow, we leave the gear down causing some drag, because, the slick, high performance glider can too easily overtake the tow plane.)

The rest is history. I flew the beautiful Jantar Standard for 42 minutes that day--climbing and turning like a silent beautiful, white bird over the clear blue skies of Texas Panhandle. During the next few years, I would take this sailplane up to 22,000 feet and make flights longer than three hours. Like a dream. But, it was real. I could be a test pilot!

Richard landing the Jantar Standard N11XH at the Panhandle, Texas airport.

(circa 1995)

(circa 1995)

Dick Wilfong, Bill Scholl (the other owner of this aircraft) and I flew the Jantar many hours over the Texas Panhandle and northeastern New Mexico. Our Jantar flying days ended when Dick moved to Austin and the local soaring club dissolved. Maybe later.

Monday, October 14, 2013

Lowell D Scales - telephone visit Saturday October 12, 2013

During the weekend of October 12th and 13th, 2013, Jeff and I attended the World Aerobatic Championships at North Texas Regional Airport in Sherman, Texas (formerly, a U.S. Air Force Base called Perrin Field). While there, Arden told me that Lowell D Scales, my mom's cousin and a World War II fighter/pursuit plane pilot--was once stationed at Perrin AFB. So, on Saturday morning, I called Lowell D at his home in Columbus, Mississippi and told him who I was and where I was. It took him a few moments to understand what was happening, but, within a few more moments, we began a 38 minute conversation that was quite a thrill for me.

I had not spoken with Lowell D since the year 2000 when we visited at Homer's funeral in Corpus Christi. We were at Jewell's house with crowds of family and friends, and, during our conversation, Lowell D asked me if I knew how he was getting back home to Columbus. I guessed Southwest Airlines. He said, no, and speaking softly and turning so nobody could hear him, told me with a smile that Barry's jet was taking him home. Aha! We talked about his upcoming trip home and I could tell that he was excited.

On that Saturday at the former Perrin Field, Lowell D and I on the phone worked up from clarifying who I was to talking about about World War II, flying, jets and Perrin Field. These are my notes, not necessary correct and not necessarily in any specific order--just what I remember from the conversation.

Lowell D served at Perrin Field and flew F-86Ds.

In 1951 he went to Korea and flew 100 missions in F-80 Shooting Stars. He said the Shooting Star was a single seat T-33.

World War II was the best time in his life--he had a powerful P-47 airplane with 8 50-caliber machine guns and he could shoot down enemy planes, trains, trucks--whatever. I told Lowell D. that I had this photo (below) and he said that he was 20 years old in this photo.

His family was like nomads--he would fly for awhile then everyone would pack up and move to another air force base where he'd fly for awhile and they'd pack up and do it again.

Lowell D is now 89, and, every morning, he eats his corn flakes, goes to see Shirley, makes sure she eats lunch, goes to some restaurant for lunch and then goes back home. That's his day. Shirley can't communicate--she mostly babbles.

For two years, he's been having having dizziness problems. It's a real pain for him.

He said that he learned to fly and got his wings flying the T-6 at Williams Field in Arizona.

He built a Lancair 320, flew it about 60 hours and sold it in 1998 because it was too physically painful for him to get into and out of the plane. The new owner, who lives in south Alabama, has flown the plane for about 1,000 hours and periodically brings it to Columbus and visits with Lowell D. Lowell D built his plane--it was complex but it came in molded parts and pieces and he did it all.

Lowell D. never lived in La Jolla but Monkey did. Lowell D. enjoyed hearing my stories about Don and I changing clothes in Aunt Sister's (Nannie Bell's and Ira's garage) and walking to the Pacific beach to go swimming.

He said that Homer flew only B-17s and that he did not remember that Homer had to finish his overseas tour of duty by flying as a courier around England for a few months.

He got shot down on December 26, 1944 while flying "Dody's Baby" (He confirmed for me the spelling of that name--DODY'S BABY). Within minutes after his bailout and the plane's crash, he was able to examine the wreckage. He said it landed pretty good for a plane without a pilot. He got another plane but it was not as good as the "mother plane" as he called it. He said, your second plane is never as good as the one you flew first. (He said that he got the name Dody because his cousins couldn't say the name Lowell D.)

He's writing his history and and has written about 40 pages. Hasn't written for awhile but said he would try to restart after our phone conversation ended.

I asked him if he had ever flown over Electra in an F-89 Scorpion (that I thought that I saw fly over Electra one day), but, he said that he had never flown and F-89. He did, however, fly over in Electra in an F-86. (Maybe that's what I saw fly low over Electra the early 1960s.)

He lived with Homer and Trixie in No Man's Land north of Electra and that is how he met Shirley who lived across the street. He and Shirley walked to town to buy ice cream and then back out to No Man's Land. I told him that my mom and dad did the same thing.

He said that he would like for the Warner brothers to come see him.

So glad I got to speak with him. I would love to visit with him for a few hours and see his photos.

I had not spoken with Lowell D since the year 2000 when we visited at Homer's funeral in Corpus Christi. We were at Jewell's house with crowds of family and friends, and, during our conversation, Lowell D asked me if I knew how he was getting back home to Columbus. I guessed Southwest Airlines. He said, no, and speaking softly and turning so nobody could hear him, told me with a smile that Barry's jet was taking him home. Aha! We talked about his upcoming trip home and I could tell that he was excited.

On that Saturday at the former Perrin Field, Lowell D and I on the phone worked up from clarifying who I was to talking about about World War II, flying, jets and Perrin Field. These are my notes, not necessary correct and not necessarily in any specific order--just what I remember from the conversation.

-----

Lowell D served at Perrin Field and flew F-86Ds.

These are 1950s era F-86Ds. Lowell D. mentioned the retractable rocket tray that fired rockets from the bottom of the plane. (from Wikipedia)

In 1951 he went to Korea and flew 100 missions in F-80 Shooting Stars. He said the Shooting Star was a single seat T-33.

World War II was the best time in his life--he had a powerful P-47 airplane with 8 50-caliber machine guns and he could shoot down enemy planes, trains, trucks--whatever. I told Lowell D. that I had this photo (below) and he said that he was 20 years old in this photo.

Lowell D Scales (P-47 pilot), Morris Barker (B-24 tail gunner) and Homer Andrews (B-17 pilot)

His family was like nomads--he would fly for awhile then everyone would pack up and move to another air force base where he'd fly for awhile and they'd pack up and do it again.

Lowell D is now 89, and, every morning, he eats his corn flakes, goes to see Shirley, makes sure she eats lunch, goes to some restaurant for lunch and then goes back home. That's his day. Shirley can't communicate--she mostly babbles.

For two years, he's been having having dizziness problems. It's a real pain for him.

He said that he learned to fly and got his wings flying the T-6 at Williams Field in Arizona.

He built a Lancair 320, flew it about 60 hours and sold it in 1998 because it was too physically painful for him to get into and out of the plane. The new owner, who lives in south Alabama, has flown the plane for about 1,000 hours and periodically brings it to Columbus and visits with Lowell D. Lowell D built his plane--it was complex but it came in molded parts and pieces and he did it all.

Photos from Arden Warner. Click to enlarge.

Lowell D. never lived in La Jolla but Monkey did. Lowell D. enjoyed hearing my stories about Don and I changing clothes in Aunt Sister's (Nannie Bell's and Ira's garage) and walking to the Pacific beach to go swimming.

He said that Homer flew only B-17s and that he did not remember that Homer had to finish his overseas tour of duty by flying as a courier around England for a few months.

He got shot down on December 26, 1944 while flying "Dody's Baby" (He confirmed for me the spelling of that name--DODY'S BABY). Within minutes after his bailout and the plane's crash, he was able to examine the wreckage. He said it landed pretty good for a plane without a pilot. He got another plane but it was not as good as the "mother plane" as he called it. He said, your second plane is never as good as the one you flew first. (He said that he got the name Dody because his cousins couldn't say the name Lowell D.)

He's writing his history and and has written about 40 pages. Hasn't written for awhile but said he would try to restart after our phone conversation ended.

I asked him if he had ever flown over Electra in an F-89 Scorpion (that I thought that I saw fly over Electra one day), but, he said that he had never flown and F-89. He did, however, fly over in Electra in an F-86. (Maybe that's what I saw fly low over Electra the early 1960s.)

He lived with Homer and Trixie in No Man's Land north of Electra and that is how he met Shirley who lived across the street. He and Shirley walked to town to buy ice cream and then back out to No Man's Land. I told him that my mom and dad did the same thing.

He said that he would like for the Warner brothers to come see him.

So glad I got to speak with him. I would love to visit with him for a few hours and see his photos.

Thursday, October 3, 2013

Flying the Cessna jet

As we climbed out from the Idaho Falls Regional Airport and turned to a heading of 131 degrees, Jason asked me if I wanted to take the controls as we climbed toward our planned altitude of 37,000 feet. I said yes and took the controls of the Cessna C510 Mustang. We could have been on autopilot but Jason knew that I'd like to get the feel of the jet as we climbed into thinner and thinner air.

We were fairly light. We had full fuel but little baggage and no passengers in the back. The sun was setting and could not be seen behind cloud layer off to the southwest. It was a beautiful evening with smooth air and light, thin widely scattered cloud wisps. A perfect evening for flying.

The Mustang was a mechanical and electronic marvel. (Ask Google to show you photos of Cessna Mustangs.) It had very few switches on the panel and it had three large Garmin G1000 screens--a Primary Flight Display (PFD) on each side and a slightly larger Multifunction Display (MFD) in the center. Other than during takeoff and landing, the autopilot flew the plane based on instructions given to it by the pilot; an amazing amount of high tech automation.

Our flight began in Dalhart, Texas at 5:13 PM CT Tuesday October 1, 2013. Jason had asked me at 1:00 PM if I wanted to fly co-pilot with him for a flight from Dalhart, Texas to Idaho Falls, Idaho and back to Dalhart, both flights that same evening. I cleared my calendar, drove to Dalhart and was ready to take off at 4 PM. The plane was ready to go and Jason was just waiting for his four passengers to arrive at the Dalhart airport. The line attendant had just sucked 30 gallons of fuel (about 200 pounds) from the tanks to account for my presence. (Full fuel, full seats and a full baggage compartment can overload the plane. The pilot must calculate and make adjustments for all weights before takeoff.)

More than you may want to know - The Cessna Mustang Specification and Description sheet states that the aircraft holds 2580 pounds of fuel and that fuel weighs 6.7 pounds per gallon. The spec sheet, however, never states the Mustang's fuel capacity in gallons. We can calculate the fuel capacity in gallons as follows: 2580 pounds divided by 6.7 lbs/gal equals 385 gallons. The pilot can use the spec sheet numbers to make precise calculation, but, can use the following numbers to make quick fuel calculations: "full fuel equals 400 gallons of fuel, and, 15 gallons of fuel weighs 100 pounds." When Jason confirmed that I would be his copilot, he assumed that I weighed 200 pounds and, therefore, asked the airport's fuel service attendant, to remove 30 gallons of fuel from the tanks.

When the four passengers arrived, they boarded the plane and sat in the cabin. I got into the right front seat, Jason removed the engine covers and walked around the plane and then Jason came aboard and closed the cabin door. In a very few minutes, he started the engines, taxied out to runway 35, informed anyone listening to unicom that were about to take flight and then he taxied onto the runway.

Lined up on runway 35, Jason held the brakes and added full power. After about seven seconds, he released the brake and off we went--V1, rotate and climb out at about 170 knots. Quite a thrill to watch all the instruments and gauges move as the ground fell away and we altered course to about 325 degrees--a direct line to Idaho Falls. Jason told unicom that we were out of there to the northwest and then he called Albuquerque Center and told them that we were off.

At about 200 feet above the ground, Jason flipped on the autopilot and set the destination altitude to 18,000 feet. After reaching 18,000 and getting cleared to 28,000 he set the new altitude and we continued higher until step by step ATC clearances got us to 36,000 feet where we leveled off and prepared for more than an hour of straight, level, scenic flight.

For an hour, Jason and I discussed the G1000, pressurization, power settings, deicing, TCAS, radar, flap settings and more. We also watched the world slide by below us--Texas farms, Pueblo, Colorado Springs, Pikes Peak, Denver, Cripple Creek, Interstate Highway 70, Aspen, Wyoming, Idaho and more. We also watched aircraft fly above, below and beside us. Never a dull moment.

At a point called top of descent, ATC told us that we could begin our decent toward the Idaho Falls airport. (Jason had told the autopilot to establish a 3 degree descent that would define a straight line from our 36,000 feet MSL cruise altitude to a point 1,000 feet above the surface of the Idaho Falls airport.) We descended on our imaginary line to pattern altitude, entered a left downwind for runway 24, dropped some flaps, dropped the gear and, after one more left turn, lined up on final for runway 24.

Jason landed (a textbook landing), taxied to the FBO and dropped off our passengers after their two hour, quiet, smooth, uneventful flight from Dalhart. It took about 15 minutes for the line attendants to add fuel, and, after pit stops and trips to the Coke machine, we were ready to say goodbye to Idaho Falls.

After refueling and buttoning up the plane, I taxied out to runway 24 and Jason took off. Before we reached 37,000 feet MSL, all was dark except for the cities and towns twinkling near and far below us, periodic white and red strobe lights passing us in the distance left and right, high and low and the glow of the G1000 brightly showing us what was going on inside the brain of this sleek, beautiful Cessna Mustang. What a ride!

ed RW

We were fairly light. We had full fuel but little baggage and no passengers in the back. The sun was setting and could not be seen behind cloud layer off to the southwest. It was a beautiful evening with smooth air and light, thin widely scattered cloud wisps. A perfect evening for flying.

Watching the sunset upon takeoff from Idaho Falls, Idaho.

(Click any photo to enlarge it.)

(Click any photo to enlarge it.)

The Mustang was a mechanical and electronic marvel. (Ask Google to show you photos of Cessna Mustangs.) It had very few switches on the panel and it had three large Garmin G1000 screens--a Primary Flight Display (PFD) on each side and a slightly larger Multifunction Display (MFD) in the center. Other than during takeoff and landing, the autopilot flew the plane based on instructions given to it by the pilot; an amazing amount of high tech automation.

The Cessna Mustang has a three-screen Garmin G1000 navigation

system (PFD screen on the left, MFD at center and PFD on the right) and

a fairly small number of fairly simple switches.

system (PFD screen on the left, MFD at center and PFD on the right) and

a fairly small number of fairly simple switches.

More than you may want to know - The Cessna Mustang Specification and Description sheet states that the aircraft holds 2580 pounds of fuel and that fuel weighs 6.7 pounds per gallon. The spec sheet, however, never states the Mustang's fuel capacity in gallons. We can calculate the fuel capacity in gallons as follows: 2580 pounds divided by 6.7 lbs/gal equals 385 gallons. The pilot can use the spec sheet numbers to make precise calculation, but, can use the following numbers to make quick fuel calculations: "full fuel equals 400 gallons of fuel, and, 15 gallons of fuel weighs 100 pounds." When Jason confirmed that I would be his copilot, he assumed that I weighed 200 pounds and, therefore, asked the airport's fuel service attendant, to remove 30 gallons of fuel from the tanks.

Cessna Mustang parked on the tarmac in Dalhart

waiting for the four passengers to arrive.

When the four passengers arrived, they boarded the plane and sat in the cabin. I got into the right front seat, Jason removed the engine covers and walked around the plane and then Jason came aboard and closed the cabin door. In a very few minutes, he started the engines, taxied out to runway 35, informed anyone listening to unicom that were about to take flight and then he taxied onto the runway.

Lined up on runway 35, Jason held the brakes and added full power. After about seven seconds, he released the brake and off we went--V1, rotate and climb out at about 170 knots. Quite a thrill to watch all the instruments and gauges move as the ground fell away and we altered course to about 325 degrees--a direct line to Idaho Falls. Jason told unicom that we were out of there to the northwest and then he called Albuquerque Center and told them that we were off.

In the the cabin section of the Cessna Mustang,

four passengers check the view of Dalhart

disappearing to the right rear.

At about 200 feet above the ground, Jason flipped on the autopilot and set the destination altitude to 18,000 feet. After reaching 18,000 and getting cleared to 28,000 he set the new altitude and we continued higher until step by step ATC clearances got us to 36,000 feet where we leveled off and prepared for more than an hour of straight, level, scenic flight.

For an hour, Jason and I discussed the G1000, pressurization, power settings, deicing, TCAS, radar, flap settings and more. We also watched the world slide by below us--Texas farms, Pueblo, Colorado Springs, Pikes Peak, Denver, Cripple Creek, Interstate Highway 70, Aspen, Wyoming, Idaho and more. We also watched aircraft fly above, below and beside us. Never a dull moment.

Don't waste too much time looking for this Southwest Airlines Boeing 737

that passed us on its way to Chicago or some other point north and east of us.

At a point called top of descent, ATC told us that we could begin our decent toward the Idaho Falls airport. (Jason had told the autopilot to establish a 3 degree descent that would define a straight line from our 36,000 feet MSL cruise altitude to a point 1,000 feet above the surface of the Idaho Falls airport.) We descended on our imaginary line to pattern altitude, entered a left downwind for runway 24, dropped some flaps, dropped the gear and, after one more left turn, lined up on final for runway 24.

On final approach to runway 24 at Idaho Falls, Idaho.

Jason landed (a textbook landing), taxied to the FBO and dropped off our passengers after their two hour, quiet, smooth, uneventful flight from Dalhart. It took about 15 minutes for the line attendants to add fuel, and, after pit stops and trips to the Coke machine, we were ready to say goodbye to Idaho Falls.

Taking on fuel at sunset in Idaho Falls, Idaho.

After refueling and buttoning up the plane, I taxied out to runway 24 and Jason took off. Before we reached 37,000 feet MSL, all was dark except for the cities and towns twinkling near and far below us, periodic white and red strobe lights passing us in the distance left and right, high and low and the glow of the G1000 brightly showing us what was going on inside the brain of this sleek, beautiful Cessna Mustang. What a ride!

ed RW

Friday, September 27, 2013

Protect that Little Black Book

During the summer of 1976, after I 'walked out' on a never-ending IBM mainframe conversion at a large bank in Indianapolis, I stood in a line at the Indianapolis airport waiting to board a plane back to Dallas. In only a few more seconds I would be on the plane, free from this computer war and headed home!

As my boarding line slowly approached the ticket taker, I glanced off to the left, and, in the distance--far down the crowded concourse--I saw my boss' head bobbing up and down. I knew immediately that he was headed my way. Bummer! I will not go back! This is my third time to walk out of this massive conversion! I'm gone. No matter what he says, I will not go back and try to salvage this abortion!

Tom got to me before I boarded the plane and said, "Richard, Richard, please come back--things will get better."

"Tom, you said that before."

"But, this time I mean it!"

"And, you said that before."

"No, Tom," I said, "I worked 100 hours this week and 100 hours last week and 100 hours the week before and I'm done. It's over. Find someone else. I'm going back to Dallas."

We talked a bit longer, and, when Tom realized that he'd lost the argument, he said, "Okay, go on home, but you'll need this." He held up a black address book.

My right hand immediately slapped my left breast pocket but my black book was gone!! Christ, I thought, I'm nothing without my black book--all those magic phone numbers!

Tom said, "Richard, you're nothing without your black book and all those magic phone numbers. You left this at the office." I grinned, said thanks and accepted my black address book from Tom.

As a nice lady took my boarding pass, I shook hands with Tom and headed for my plane.

Tom turned around and went back to that abortion that was continuing at some big bank in downtown Indianapolis.

I flew back to Dallas.

Even chain-smoking Tom knew that even the hardest working computer nerds could work even better when they had all the right phone numbers.

--------------

In 1979, when I owned my own company in Amarillo, Tom (now my 'former' boss) called me from St Louis and told me that another big mainframe conversion was in progress at a big bank there. Fifteen high-dollar computer gurus were stumbling all over themselves, the conversion was two weeks late, the company was paying a fine every day for not giving up the old mainframe computer and Tom needed help.

You can read that story in a blog called "St Louis Blues."

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

SCUBA diving in one easy lesson - a Pacific adventure

In April of 1965, Bill Macklin and I stashed our suitcases in the trunk of my 1956 Chevy four-door hardtop and left Wichita, Kansas on a 1,799 mile trip to Acapulco, Mexico. (I'm writing this story on August 2, 2013 and I cannot recall why Mac and I chose to make such a long trip. But, in 1965, I was 21 years old and much smarter than I am today, so, I'm sure we, or I, had a good reason to drive nearly 4,000 miles.)

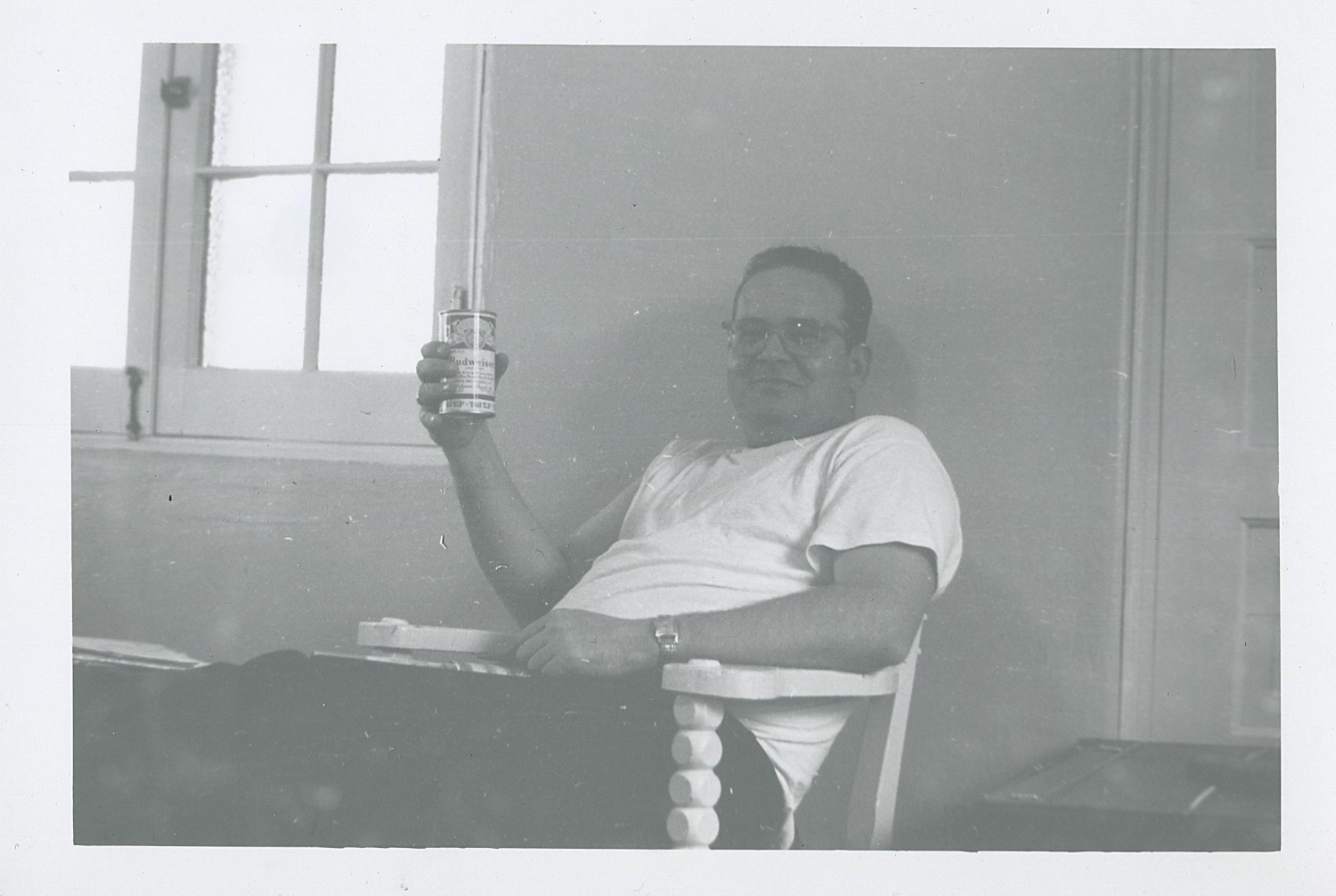

Mac and I packed quite a few clothes--as you might expect--but, we also took many cans of Budweiser. Mac was quite good at tossing down the Budweisers and, I'm sorry to say, that in a few short years that resulted in an early death. But, for now, it's on to Acapulco.

We drove south through Dallas, Texas, through Monterrey, Mexico (where Mac enjoyed his last Budweiser--see photo of Mac drinking the last can--it would be Carta Blanca for the rest of the trip), through Mexico City (where I climbed the pyramids and bought a black obsidian carved head that has graced my desk now for more than 16,000 days) and on to Acapulco where we checked in to the Hotel Costa Azul.

During our first day on the beach, we met and befriended a family of teenagers that had come to Acapulco from Yucatan. They enjoyed practicing their English and we enjoyed sharing our vacations. During our week in Acapulco, we saw them often and shared a few meals. And, for a few years, we exchanged letters but that eventually stopped. (As of this writing, I still have the letters.)

Somewhere along the beach road in Acapulco, I saw a sign that said SCUBA lessons $18. Sounded good to me--I was 21 and needed to learn how to SCUBA dive. A day or two after seeing the sign, I left Mac at a nearby bar that he liked (Mac's idea), asked him to await my return and drove to the SCUBA school pier that extended out into the Acapulco bay. Two Mexican boys about 17 years of age, barefoot and dressed in brightly colored Speedos, understood little or no English but did understood my request, either because I pointed to the "SCUBA lesson" sign or because I held in my hand eighteen dollars "American." They accepted my money, indicated that I should don my swimsuit and then pointed to a chair where I should wait. I silently watched them prepare the shop for our departure and hoped that I was doing the right thing.

Shortly, they loaded three SCUBA tanks, masks, snorkels, fins, spearguns, net bags and a few other things into an outboard motor boat and motioned me aboard. I asked them when the lessons would begin, but, all they did was nod yes and assure me of something they thought I understood but didn't. I took my seat and off we went into the bay. I knew the lessons would begin shortly.

But, no. Instead of venturing out a bit and stopping, we motored at the boat's top speed across the bay and into the Pacific Ocean. Enroute, I saw the cliff where divers performed their death defying dives and high above the water, the house that I had learned during yesterday's bus tour belonged to John Wayne. Heading north along the Pacific coast, I saw much of the Mexican coastline. When our high speed ride exceeded thirty minutes, the word 'kidnapped' visited my thoughts?

Finally, the boat slowed and stopped. One boy threw out the anchor while the other donned his SCUBA gear--BC, tank, fins, weight belt and mask. He indicated that I was to watch him and, then, he sat on the side of the boat and rolled backwards into the water. Duly noted.

Number two then dressed me--BC, tanks, fins, weight belt, mask and snorkel. He showed me the reserve air valve and made sure I understood--when I ran out of air, I was to turn this knob on the back of my tank. Duly, duly noted. Thus ended my SCUBA lessons. Number two donned his gear and urged me toward the boy treading water by the boat. I guess I know how to SCUBA dive.

I sat on the side of the boat, held my mask with one hand and backup regulator with the other, and, then, rolled backwards into the water. While I bobbed in the water, number one worked me over tightening, pulling, turning, twisting, and, within seconds, signalled 'okay' to number two and me. The boy in the boat handed down spears and nets, grabbed his own spear and net and leaped into the water. We all mumbled something in two languages, grinned like we knew what we were doing, shoved regulators in our mouths, positioned our masks, pressed the relief button on our BCs and began sinking slowly into the crystal clear water of the Pacific.

I was entranced! I still see the clear blue water, fish I could not count, a sandy bottom far below and my two friends paddling away and motioning for me to follow.

I did. We swam and I was hooked on diving. Within seconds, any fear that I had disappeared and I was in heaven. I brought up the rear and watched as my two diving buddies speared fish after fish and placed them in their net bags. Only once did I get close enough to spear a round, flat, white fish (Flounder?). My spearing technique, however, was, unfortunately, fatally flawed--I merely turned the fish around, rubbed my hand against his spiny brown back side, pulled quickly away and decided that my forte here was sightseeing. Let the Speedo team collect all the fish they could.

After thirty minutes of seeing and feeling unbelievable beauty, my breathing slowed. I tapped one boy's tank and pointed at mine. They stopped, activated my reserve air, watched to be sure that I was 'better,' nodded 'good' and headed out to seek more dinner. I pointed up toward the boat and tried to mumble, "Shouldn't we be going back?" but they were gone. Breathing easier but thinking I was short of air, I reluctantly followed and the beauty did not end..

Minutes later, they indicated they were through and pointed up toward the boat. I knew that air was low but I really hated to leave this beautiful, beautiful place. (I've been SCUBA diving more than one hundred times since this trip and have never seen water as beautiful as this Pacific shore area just north of Acapulco.) We swam toward the anchor rope and, fifteen to twenty feet below the boat, stopped and held the rope. They pointed to their watches and showed me some fingers. I understood we had to wait for something that, a few years later, I would understand.

Finally, we all climbed into the boat, ditched our SCUBA gear and headed for the "SCUBA diving lessons $18" sign nearly an hour away in Acapulco. I enjoyed the trip back but was disappointed that I couldn't share my experiences with my diving partners who had just visited a world I never imagined but who spoke a language I could not understand.

An hour later we arrived at the pier. I shook hands with my SCUBA teachers (?) and headed for the car. As I was about to get into the car, I glanced back at the boys working on their catch of the day, scanned the beautiful bay, looked out at the white frothing Pacific and told myself, "Wow! I went SCUBA diving!" I hope Mac had fun while I was gone. I'm sure he did.

-----

Nine years after Mac and I visited Acapulco, I took a SCUBA diving course at the Amarillo YMCA and learned about some of the diving risks that I had taken in Acapulco back in 1965. But, I was 21. What do you do?

The 1956 Chevy (left) that Mac and I drove to and from Acapulco, Mexico. I bought the car, my first car, for $400 in 1965, the year that I turned 21. I kept it until 1968 when I replaced it with a 1968 Volkswagen bug. That's Ed Kinney's Chevy Corvair on the right.

Mac and I packed quite a few clothes--as you might expect--but, we also took many cans of Budweiser. Mac was quite good at tossing down the Budweisers and, I'm sorry to say, that in a few short years that resulted in an early death. But, for now, it's on to Acapulco.

We drove south through Dallas, Texas, through Monterrey, Mexico (where Mac enjoyed his last Budweiser--see photo of Mac drinking the last can--it would be Carta Blanca for the rest of the trip), through Mexico City (where I climbed the pyramids and bought a black obsidian carved head that has graced my desk now for more than 16,000 days) and on to Acapulco where we checked in to the Hotel Costa Azul.

During our first day on the beach, we met and befriended a family of teenagers that had come to Acapulco from Yucatan. They enjoyed practicing their English and we enjoyed sharing our vacations. During our week in Acapulco, we saw them often and shared a few meals. And, for a few years, we exchanged letters but that eventually stopped. (As of this writing, I still have the letters.)

This is the family that we met during our trip to Acapulco--siblings and cousins all from Yucatan. Right rear wearing short sleeve shirt and looking at camera is yours truly--Richard Warner.I have many Acapulco stories--some that I will tell in this and other postings, some that I will not. SCUBA is the subject of this story.

Somewhere along the beach road in Acapulco, I saw a sign that said SCUBA lessons $18. Sounded good to me--I was 21 and needed to learn how to SCUBA dive. A day or two after seeing the sign, I left Mac at a nearby bar that he liked (Mac's idea), asked him to await my return and drove to the SCUBA school pier that extended out into the Acapulco bay. Two Mexican boys about 17 years of age, barefoot and dressed in brightly colored Speedos, understood little or no English but did understood my request, either because I pointed to the "SCUBA lesson" sign or because I held in my hand eighteen dollars "American." They accepted my money, indicated that I should don my swimsuit and then pointed to a chair where I should wait. I silently watched them prepare the shop for our departure and hoped that I was doing the right thing.

Shortly, they loaded three SCUBA tanks, masks, snorkels, fins, spearguns, net bags and a few other things into an outboard motor boat and motioned me aboard. I asked them when the lessons would begin, but, all they did was nod yes and assure me of something they thought I understood but didn't. I took my seat and off we went into the bay. I knew the lessons would begin shortly.

But, no. Instead of venturing out a bit and stopping, we motored at the boat's top speed across the bay and into the Pacific Ocean. Enroute, I saw the cliff where divers performed their death defying dives and high above the water, the house that I had learned during yesterday's bus tour belonged to John Wayne. Heading north along the Pacific coast, I saw much of the Mexican coastline. When our high speed ride exceeded thirty minutes, the word 'kidnapped' visited my thoughts?

Finally, the boat slowed and stopped. One boy threw out the anchor while the other donned his SCUBA gear--BC, tank, fins, weight belt and mask. He indicated that I was to watch him and, then, he sat on the side of the boat and rolled backwards into the water. Duly noted.

Number two then dressed me--BC, tanks, fins, weight belt, mask and snorkel. He showed me the reserve air valve and made sure I understood--when I ran out of air, I was to turn this knob on the back of my tank. Duly, duly noted. Thus ended my SCUBA lessons. Number two donned his gear and urged me toward the boy treading water by the boat. I guess I know how to SCUBA dive.

I sat on the side of the boat, held my mask with one hand and backup regulator with the other, and, then, rolled backwards into the water. While I bobbed in the water, number one worked me over tightening, pulling, turning, twisting, and, within seconds, signalled 'okay' to number two and me. The boy in the boat handed down spears and nets, grabbed his own spear and net and leaped into the water. We all mumbled something in two languages, grinned like we knew what we were doing, shoved regulators in our mouths, positioned our masks, pressed the relief button on our BCs and began sinking slowly into the crystal clear water of the Pacific.

I was entranced! I still see the clear blue water, fish I could not count, a sandy bottom far below and my two friends paddling away and motioning for me to follow.

I did. We swam and I was hooked on diving. Within seconds, any fear that I had disappeared and I was in heaven. I brought up the rear and watched as my two diving buddies speared fish after fish and placed them in their net bags. Only once did I get close enough to spear a round, flat, white fish (Flounder?). My spearing technique, however, was, unfortunately, fatally flawed--I merely turned the fish around, rubbed my hand against his spiny brown back side, pulled quickly away and decided that my forte here was sightseeing. Let the Speedo team collect all the fish they could.

After thirty minutes of seeing and feeling unbelievable beauty, my breathing slowed. I tapped one boy's tank and pointed at mine. They stopped, activated my reserve air, watched to be sure that I was 'better,' nodded 'good' and headed out to seek more dinner. I pointed up toward the boat and tried to mumble, "Shouldn't we be going back?" but they were gone. Breathing easier but thinking I was short of air, I reluctantly followed and the beauty did not end..

Minutes later, they indicated they were through and pointed up toward the boat. I knew that air was low but I really hated to leave this beautiful, beautiful place. (I've been SCUBA diving more than one hundred times since this trip and have never seen water as beautiful as this Pacific shore area just north of Acapulco.) We swam toward the anchor rope and, fifteen to twenty feet below the boat, stopped and held the rope. They pointed to their watches and showed me some fingers. I understood we had to wait for something that, a few years later, I would understand.

Finally, we all climbed into the boat, ditched our SCUBA gear and headed for the "SCUBA diving lessons $18" sign nearly an hour away in Acapulco. I enjoyed the trip back but was disappointed that I couldn't share my experiences with my diving partners who had just visited a world I never imagined but who spoke a language I could not understand.

An hour later we arrived at the pier. I shook hands with my SCUBA teachers (?) and headed for the car. As I was about to get into the car, I glanced back at the boys working on their catch of the day, scanned the beautiful bay, looked out at the white frothing Pacific and told myself, "Wow! I went SCUBA diving!" I hope Mac had fun while I was gone. I'm sure he did.

-----

Nine years after Mac and I visited Acapulco, I took a SCUBA diving course at the Amarillo YMCA and learned about some of the diving risks that I had taken in Acapulco back in 1965. But, I was 21. What do you do?

Sometime it's hard to join the U.S. Air Force

On Sunday afternoon July 1, 1962, I sat in the car with my mom and dad at the corner of Cleveland and Main Streets in Electra, Texas. The windows were down, it was hot and I was eager to get on the air conditioned bus that would take me from Electra, Texas, to Dallas, to the U.S. Air Force and to the world.

I was 18 years old and had been out of high school one month. I worked at the local IGA grocery store for the past few years, and, after graduating from high school, had spent one more month working there while saying my goodbyes to the people and places that had been my life for the past 10 years. My mom told me that she had promised herself she would not cry when I boarded the bus. She had cried when Arden left, cried when Curtis left, but, she would not cry when I left. Bet she did.

We stepped out of the car as the Continental Trailways bus pulled up to the curb and stopped. No one got off, no one got on. We walked up to the door as the driver stepped down. "I'm going to Dallas," I said. He took my ticket and I boarded the bus. I sat in a seat that allowed me to wave at my mom and dad, he was wearing khakis and and a long sleeve white shirt and my mom was wearing a light print dress and had short hair. I took a photo of them in my mind.

-----

On Monday morning, I got up at the freezing-cold Lawrence Hotel in downtown Dallas and walked two blocks to the Air Force induction station. I identified myself, completed a few forms and and joined about 40 other 18 year old young men (we thought we were men) for our physical. I assumed that all of us would spend tonight at Lackland AFB in San Antonio. It was not to be.

Things went ary as our physical was ending. Forty 18 years old boys wearing only their tighty whities sat side by side on a long bench against the wall of a small gym. Five or six white frocked doctors entered the room and closed the doors. Someone told us to leave our underwear on the bench and stand shoulder to shoulder on that black line.

We stripped and stepped forward. For the next 30 minutes, the five doctors went up and down the line probing, prodding, listening with stethoscopes, feeling here, pushing there, shining lights here, sticking tongue depressors there, and, in general, making sure that this amazing example of human flesh was up to what the U.S. Air Force was about to demand of it. We already knew we were amazing.

The doctors gathered at the far end of the room while forty of us stood naked on that black line waiting for the word to put on our underwear, return to our lockers, get dressed and head out. We were ready! But, first, we waited.

The doctors made notes, pointed back at him or him, moved file folders here and there, walked back and asked one of us a question and seemed ready to call it a day. Then, then...

One doctor walked the line all the way to the end, turned around, came halfway back and stopped about eight feet in front of me looking at my waist. That cleared my mind! His head moved back and forth as he studied my hips. When my next-shoulder neighbors glanced down at my hips to see what was up--uh,what was going on, I gave them both one of those, "I'm not happy with what you're doing" looks. Both straightened up.

Doctor 1 called doctor 2 over. They muttered something about me and shared the study of my naked waist. Doctor 1 moved closer to me, got down on his knees and moved his head back and forth obviously entranced by something about my waist. Doctors 3, 4 and 5, wondering what they had missed, joined doctors 1 and 2. The naked to-be airmen 1 through 19 and 21 through 40 all moved forward--off the black line!--to see what was attracting everybody's attention. I would not look down because, well, I just did not want to look down.

Now, with everybody but God looking at my waist, doctor 1 reached up with both hands and touched my hips. He moved my hips a bit, mumbled something to the white frocked crowd gathered around him, and got a unanimous agreement of nods and supporting mumbles. What is going on!

Doctor 1 stood up, told me to put my underwear on and follow him. Watch how fast I can do that.

Doctor one directed me to a table in his office, and, using a tape, measured my legs. He pushed and pulled my feet and heels, rolled my legs left and right and asked me when I broke my leg. I said I never did. He said, "Your right leg is 1 inch longer that your left leg--did you know that?" No. He said that I should get dressed and check in at the lobby. At the lobby, the nice lady told me that I had pneumonia (pneumonia!) and she was giving me a bus ticket back to Electra!

End of story

Because I did not want to return to Electra--I had already checked out of Electra--I opted to join my brother in Fort Worth where I could plan my next move. I went to Fort Worth.

One week later, I explained my plight by telephone to the Fort Worth Air Force recruiter. Ten minutes later, he called me back, drove straight to my brother's house, took me straight to the Dallas induction center and led me to a classroom where I waited most of the day. About midday, forty recruits joined me in the classroom where we stood and swore allegiance to the stars and stripes. Forty one of us promptly left the induction center for Lackland AFB in San Antonio.

I'm sure the U.S. Air Force knew what they were doing on that first and second Monday of July 1962, but, I did not.

I was 18 years old and had been out of high school one month. I worked at the local IGA grocery store for the past few years, and, after graduating from high school, had spent one more month working there while saying my goodbyes to the people and places that had been my life for the past 10 years. My mom told me that she had promised herself she would not cry when I boarded the bus. She had cried when Arden left, cried when Curtis left, but, she would not cry when I left. Bet she did.

We stepped out of the car as the Continental Trailways bus pulled up to the curb and stopped. No one got off, no one got on. We walked up to the door as the driver stepped down. "I'm going to Dallas," I said. He took my ticket and I boarded the bus. I sat in a seat that allowed me to wave at my mom and dad, he was wearing khakis and and a long sleeve white shirt and my mom was wearing a light print dress and had short hair. I took a photo of them in my mind.

-----

On Monday morning, I got up at the freezing-cold Lawrence Hotel in downtown Dallas and walked two blocks to the Air Force induction station. I identified myself, completed a few forms and and joined about 40 other 18 year old young men (we thought we were men) for our physical. I assumed that all of us would spend tonight at Lackland AFB in San Antonio. It was not to be.

Things went ary as our physical was ending. Forty 18 years old boys wearing only their tighty whities sat side by side on a long bench against the wall of a small gym. Five or six white frocked doctors entered the room and closed the doors. Someone told us to leave our underwear on the bench and stand shoulder to shoulder on that black line.

We stripped and stepped forward. For the next 30 minutes, the five doctors went up and down the line probing, prodding, listening with stethoscopes, feeling here, pushing there, shining lights here, sticking tongue depressors there, and, in general, making sure that this amazing example of human flesh was up to what the U.S. Air Force was about to demand of it. We already knew we were amazing.

The doctors gathered at the far end of the room while forty of us stood naked on that black line waiting for the word to put on our underwear, return to our lockers, get dressed and head out. We were ready! But, first, we waited.

The doctors made notes, pointed back at him or him, moved file folders here and there, walked back and asked one of us a question and seemed ready to call it a day. Then, then...

One doctor walked the line all the way to the end, turned around, came halfway back and stopped about eight feet in front of me looking at my waist. That cleared my mind! His head moved back and forth as he studied my hips. When my next-shoulder neighbors glanced down at my hips to see what was up--uh,what was going on, I gave them both one of those, "I'm not happy with what you're doing" looks. Both straightened up.

Doctor 1 called doctor 2 over. They muttered something about me and shared the study of my naked waist. Doctor 1 moved closer to me, got down on his knees and moved his head back and forth obviously entranced by something about my waist. Doctors 3, 4 and 5, wondering what they had missed, joined doctors 1 and 2. The naked to-be airmen 1 through 19 and 21 through 40 all moved forward--off the black line!--to see what was attracting everybody's attention. I would not look down because, well, I just did not want to look down.

Now, with everybody but God looking at my waist, doctor 1 reached up with both hands and touched my hips. He moved my hips a bit, mumbled something to the white frocked crowd gathered around him, and got a unanimous agreement of nods and supporting mumbles. What is going on!

Doctor 1 stood up, told me to put my underwear on and follow him. Watch how fast I can do that.

Doctor one directed me to a table in his office, and, using a tape, measured my legs. He pushed and pulled my feet and heels, rolled my legs left and right and asked me when I broke my leg. I said I never did. He said, "Your right leg is 1 inch longer that your left leg--did you know that?" No. He said that I should get dressed and check in at the lobby. At the lobby, the nice lady told me that I had pneumonia (pneumonia!) and she was giving me a bus ticket back to Electra!

End of story

Because I did not want to return to Electra--I had already checked out of Electra--I opted to join my brother in Fort Worth where I could plan my next move. I went to Fort Worth.

One week later, I explained my plight by telephone to the Fort Worth Air Force recruiter. Ten minutes later, he called me back, drove straight to my brother's house, took me straight to the Dallas induction center and led me to a classroom where I waited most of the day. About midday, forty recruits joined me in the classroom where we stood and swore allegiance to the stars and stripes. Forty one of us promptly left the induction center for Lackland AFB in San Antonio.

I'm sure the U.S. Air Force knew what they were doing on that first and second Monday of July 1962, but, I did not.

Dumber than dirt - El Paso trip in Aerostar 200

On Friday evening March 24, 1972, Don Harper and I climbed aboard an Aerostar 200 N9484V (also known as a Mooney M20C Ranger) and left Town and Country Airpark Lubbock, Texas for a 2.5 hour flight to El Paso, Texas. This was a great airplane and I had recently completed my Instrument checkride in it. It was about two years old, looked like it was brand new, was fairly quiet, had retractable gear, was pretty fast and was a dream to fly.

Don and I were headed to El Paso to help State National Bank install some new banking and operating system software on their mainframe computer. I would return to Lubbock alone on Monday.

About 30 minutes out of Lubbock, the sun set off to the west as approached the mountains of New Mexico. I flew the plane continuously because it had no autopilot but it did have the Mooney wing-leveler that made long flights a little more comfortable. The engine was purring, fuel was fine, Don and I ate our snacks and we talked about our plans for the weekend.

Soon the sky was pitch black, stars were visible off to the west but to the east, a full moon reflected off of my left wing. A beautiful night for flying--smooth, clear, and, so black outside that we could see towns 50 miles away. Actually, there aren't many towns in southeast New Mexico.

Blink! Every light in the cockpit went out. Crap! (Aviator term--you wouldn't understand.) I got my flashlight and, Don and I, working together, checked all the circuit breakers. Looked good. We pulled the POH (Pilot Operating Handbook) and studied that but no joy--the lights stayed off. I told Albuquerque Center that we had lost our panel lights, were working on the problem and would be continuing on. While I held the plane level, Don scrounged around and came up with two more flashlights--all were bright and all obviously had good batteries.

I could fly the plane with one hand while holding the flashlight in the other hand, but, when we got to El Paso, flying the approach and landing the plane would be a little tough with only one hand. So, I taught Don some pilot stuff--when I say airspeed, point the flashlight here, altitude--here, HSI--here, comm radio--here, gear handle--here, etc. He practiced with one flashlight so that we would always have two flashlights for backup.

Within an hour, the lights of El Paso hove into view and we began our descent. Don was an expert--with a flashlight in each hand and one in his mouth, he responded like an orchestra leader to my every command. The plane flew perfectly, the landing pattern was easy, I flew a right base for runway 4, Don found the altimeter and airspeed indicators exactly when I needed him to, and, the tower assured us that we had external lights and a landing light. Nice.

The landing was smooth, and, on the ground and parked, I asked the FBO (Fixed Base Operator) to check the plane tomorrow and I told them that I would be leaving the airport for Lubbock on Monday afternoon. We cleared the plane of baggage and clothes and made a mental note to buy some extra batteries before my next flight.

-----

Now the 'dumber than dirt' part of this story

Don's girlfriend, with her friend were waiting to pick us up. We packed the car trunk with our stuff, Don and Julie got in back and I sat in front as we headed for dinner at Don's favorite El Paso restaurant. Speeding west on the I-10 freeway, driving an unfamiliar car, managing the nighttime traffic and hearing driving directions from two people in the back seat was tough enough for our driver to handle, so, she asked me to get her cigarettes out of her purse and light one for her. That sounded easy enough.